The Making of Hooks

Manufacturing Process

The manufacturing of fishing hooks has become mechanized, and in some instances fully automated, utilizing very complex machinery. The essential hook making procedure begins with the use of wire, usually a high carbon content steel. Occasionally steel alloys are also used. Once a wire of a proper diameter has been selected, it is cut to the exact predetermined length that will be required for a finished hook of a particular size and style. The next step is to "point" the wire. While in the past, the points were hand-filed by experienced craftsmen, today they are either shaped on a grinding machine or else they are cut on the diagonal to form a point. Following the pointing process, if a tapered eye is specified in the hook design, then the forward end of the wire is ground to the appropriate taper.

The next requirement is to create the hook's barb which is accomplished by cutting into the wire at an acute angle and raising a small sliver of metal resulting in a barb. Here, too, the depth of the slice must be extremely precise since too deep a cut would substantially reduce the hook's strength.

Shaping the hook, or forming a bend, is next achieved by physically bending the wire to conform to the shape of an established form. Tool makers create forms to the size and shape of individual hook styles, and must make a form for each hook size within a style. These resulting dies exactly match the inside radius of the hook shape desired. With the wire point and barb firmly held in position, the wire is then forced to wrap, or bend, around the selected die. The result of this procedure is a wire incorporating the desired shape of the bend. The die configuration determines whether the shape is a Sproat, Kirby, Limerick, etc.

Forging is a term applied to a process of forming metal. In hook making, it refers to the flattening of the round wire in such a manner as to increase its strength in one plane, or direction. Commonly, hooks are forged on both sides beginning at a point behind the barb, and extending throughout the bend up to the hook shank. Often the forging will include much of the hook shank as well. By flattening both sides of the hook, the strength along a theoretical straight line of pull is increased.

The process of forging is accomplished by simply placing individual hooks into a press which flattens the round wire to a controlled thickness.

The last stage of forming the typical hook is the creation of the "eye". Again the procedure involves bending the forward end of the wire around a form of the appropriate diameter. The form in this instance is simply a metal peg. The hook is held stationary while the forward end of the wire is wrapped around this peg. This seems a simple enough process when one envisions large hook eyes being formed, but for the tiny hooks, it might be remembered that this peg is smaller in thickness than the hook itself. A final bend of the hook wire may now be made where the eye is to be "turned up" or "turned down".

Chemical sharpening is a term which has only recently been used in connection with hook making. It refers to a rather simple process whereby hooks, once completely formed, are immersed into an acid bath which dissolves any minute burrs or abrasions which occurred during manufacture. The result, under proper controls, is a cleaner metal surface and, thus, sharper hooks. An increased number of hook producers are now now utilizing this technique although they may refer to it by different terms. Mustad, Tiemco and Daiichi say chemically sharpened, whereas Eagle Claw calls it Laser Sharpening and Partridge names it Flashpointing.

The soft carbon steel wire must be hardened to improve strength. This is accomplished by tempering the metal. Hooks are placed in an oven which heats them throughout, and they are then immersed in a liquid coolant, often a closely guarded secret formula, which brings about a rapid decrease in temperature. This process hardens the metal, significantly increasing its resistance to bending. Too much tempering, however, and the hook becomes brittle.

The next stage of the production flow is to clean the metal in preparation of its receiving a final protective coating. There are various means employed but they are represented by the tumbling process whereby the hooks are cleaned with an abrasive.

Applying the hook's finish is the last step before a final inspection and packaging. Most all of the common hooks have a finish described as "bronze". This simply refers to the approximate color of the hook which results from applying one or more coats of clear, or amber, lacquer to the hooks surface. Trays of hooks are coated with lacquer, they are then heated or baked in ovens, and a second coat is often applied and the process repeated. Black finishes, sometimes referred to as "Japanned Black", are simply a pigmented lacquer used in the same manner. Almost any color can be applied at this stage but bronze, black and red have been those colors used most commonly. For fly hooks, Silver and gold finishes can, optionally, be used. Here the finish is achieved by electroplating rather than by lacquering.

Nomenclature of Hooks

Despite proposals which have appeared over many decades, the hook making industry has made little progress in arriving at any standard on which anglers may rely. For example, between different manufacturers hook sizes are often determined by differing proprietary standards. One producers standard size 14 hook may have a gape equal to another company's standard size 18 hook. Shank lengths similarly vary, while descriptions of wire weight and the shape of the bend often serve only to confuse buyers.

Gap or Gape Gap or Gape

There is no confusion here about the measurement, which is the shortest distance between the hook point and hook shank. Among the hook producers, those located in English speaking countries have traditionally used "gape" whereas the term "gap" is used exclusively by manufacturers in countries whose language is other than English.

Shape or Bend

Both terms have been utilized to describe a hook's particular curvature. It seems to me more proper to use the term "bend" as a noun referring to the specific part of the hook, and to use the term "shape" as a descriptive adjective. Thus, we would refer to the "shape of the bend". A "sproat" bend or "limerick" bend, where both sproat and limerick are terms used to describe the shape of the bend.

Offset Bends

If the point of a hook is not in the same plane as the shank, i.e., if it is bent to one side, it is termed as "offset", as opposed to straight. The terms "kirbed" or "reversed" further signify whether the point is offset to the right or left side. Some manufacturers simply state "offset" in describing their hooks, while others provide us a more complete description.

Shank Length

The terminology shank length has traditionally signified the measurement from behind the hook eye to that point where the hook begins to curve. Although it has been suggested that this measurement might be called "body length", and it's also been argued that the measurement might extend to include the eye, these ideas have gathered only limited support. There is a tendency to favor the more traditional "shank length" as the descriptive standard.

However, manufacturers often designate hook shank length as being 1X, or 2X, or 3X long (or short). This terminology means that the hook is longer than that producer's "standard" shank length for the same style hook. A 2X long shank is equal in length to the shank of the standard hook which is two sizes larger. For example, a size 12 hook, 2X long, has a hook shank length equal to the same style's "standard" hook in a size 10. Notice that for purposes of this length designation, it is assumed that hook sizes change in increments of one. To further complicate matters, not all hook producers adhere to this formula, and inconsistencies abound.

Point & Spear

The term point describes both the sharp tip end of a hook as well as the entire portion ranging from that tip to the hook barb. Spear, on the other hand, represents that portion of the hook measured from the bottom of the bend, forward to the tip of the point.

Throat

The distance from the front end of the hook point to the furthest depth of the bend is called the throat. If this distance is too short it is agreed that there is a greater chance that a fish might free itself from the hook.

Heel

The term heel is customarily used to refer to that portion of the bend which is affected by the forging process.

Eye

Represents the forward part of the hook, to which the fishing line or leader is attached. Modern hooks are either ball (sometimes called "ringed", a confusing designation as you will soon note) or looped, and the end of the wire is either tapered or untapered. The finished eye is either straight, or is turned up or turned down. On a very few hook models the eye is turned 90 degrees to a position in the same plane as that of the hook bend. This style eye is also termed "ringed".

Testing Procedures

Shank Length: Measured from a point immediately behind the hook eye to the beginning of the bend. Essentially, this represents the usable length of the hook shank. Shank Length: Measured from a point immediately behind the hook eye to the beginning of the bend. Essentially, this represents the usable length of the hook shank.

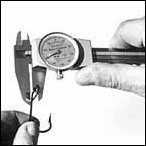

Gape: Is the distance between the point and the hook shank. While it has been customarily accepted that there is a relatively standard relationship between gape and hook size, a review of the actual measurements will reveal this is not true. At the extreme we found gapes of 4 mm. on hooks which were sized all the way from #10 to #18. Gape: Is the distance between the point and the hook shank. While it has been customarily accepted that there is a relatively standard relationship between gape and hook size, a review of the actual measurements will reveal this is not true. At the extreme we found gapes of 4 mm. on hooks which were sized all the way from #10 to #18.

Weight: Was calculated using a sensitive jeweler's balance, weighing ten or more hooks at a time, and establishing the average weight. Weight: Was calculated using a sensitive jeweler's balance, weighing ten or more hooks at a time, and establishing the average weight.

Wire Diameter: Measurements were taken on the round unforged portion of the hook wire using a blade micrometer. Because of rounding errors, measurements may vary ±0.03 mm. Wire Diameter: Measurements were taken on the round unforged portion of the hook wire using a blade micrometer. Because of rounding errors, measurements may vary ±0.03 mm.

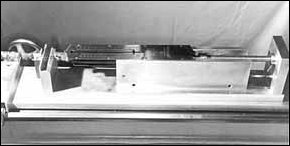

Bend Resistance: It was needed to establish some measure of each hook's strength, compared with other hooks. It was deemed that the greatest opportunity for hook failure was when the point was subject to maximum leverage, and that the risk of "practical" failure was likely to occur when the hook point moved 60 degrees from its original position, or if it broke before attaining 60 degrees. To make such measurements,a hook-holding device of aluminum stock was affixed to a metalworking lathe bed that would allow the application of steady, gradual pressure.

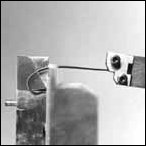

The hook was positioned so that the tip of the point remained stationary as force was applied through a wire inserted in the hook eye. Behind the hook an adjustable plate allowed us to align the natural hook point with a line, (our zero line) and this plate also contained a mark 60 degrees from zero so that we could visibly detect our theoretical point of failure. As force was applied, a scale provided a reading which is called "bend resistance", or the number of ounces of force required to bend the hook to 60 degrees. The hook was positioned so that the tip of the point remained stationary as force was applied through a wire inserted in the hook eye. Behind the hook an adjustable plate allowed us to align the natural hook point with a line, (our zero line) and this plate also contained a mark 60 degrees from zero so that we could visibly detect our theoretical point of failure. As force was applied, a scale provided a reading which is called "bend resistance", or the number of ounces of force required to bend the hook to 60 degrees.

Two scales were employed; one was used for larger hooks measured in 2 ounce increments, while a second provided more accurate 1 ounce increments for smaller hooks. Two hooks of each size were tested and the results were accepted if both hooks provided identical scale readings. Up to five more hooks were tested if it was found that there was any variance in the original two measurements. Two scales were employed; one was used for larger hooks measured in 2 ounce increments, while a second provided more accurate 1 ounce increments for smaller hooks. Two hooks of each size were tested and the results were accepted if both hooks provided identical scale readings. Up to five more hooks were tested if it was found that there was any variance in the original two measurements.

Fishing Tip : Fishing Tip : |

|

| Why not contact fishSA.com about your Fishing Tip |

|

|